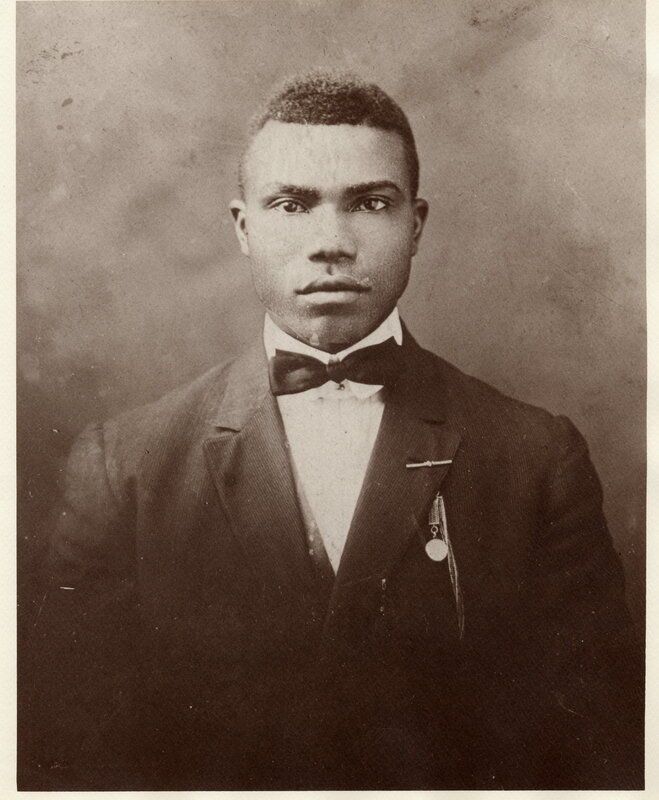

Robert Athlyi Rogers

1891 – 1931

Visionary, Spiritual leader, Activist, Thinker, Prophet, Writer

Born in Anguilla in 1891, Robert Athlyi Rogers joined the voices that were agitating for the empowerment of black people. He founded his own church in Newark, N.J with an outreach ministry in the Americas, the Caribbean and Africa. He published The Holy Piby in 1924, a compilation of his principles and visions for spiritual growth. His Shepherd’s Prayer is the foundation of the Rastafari Creed.

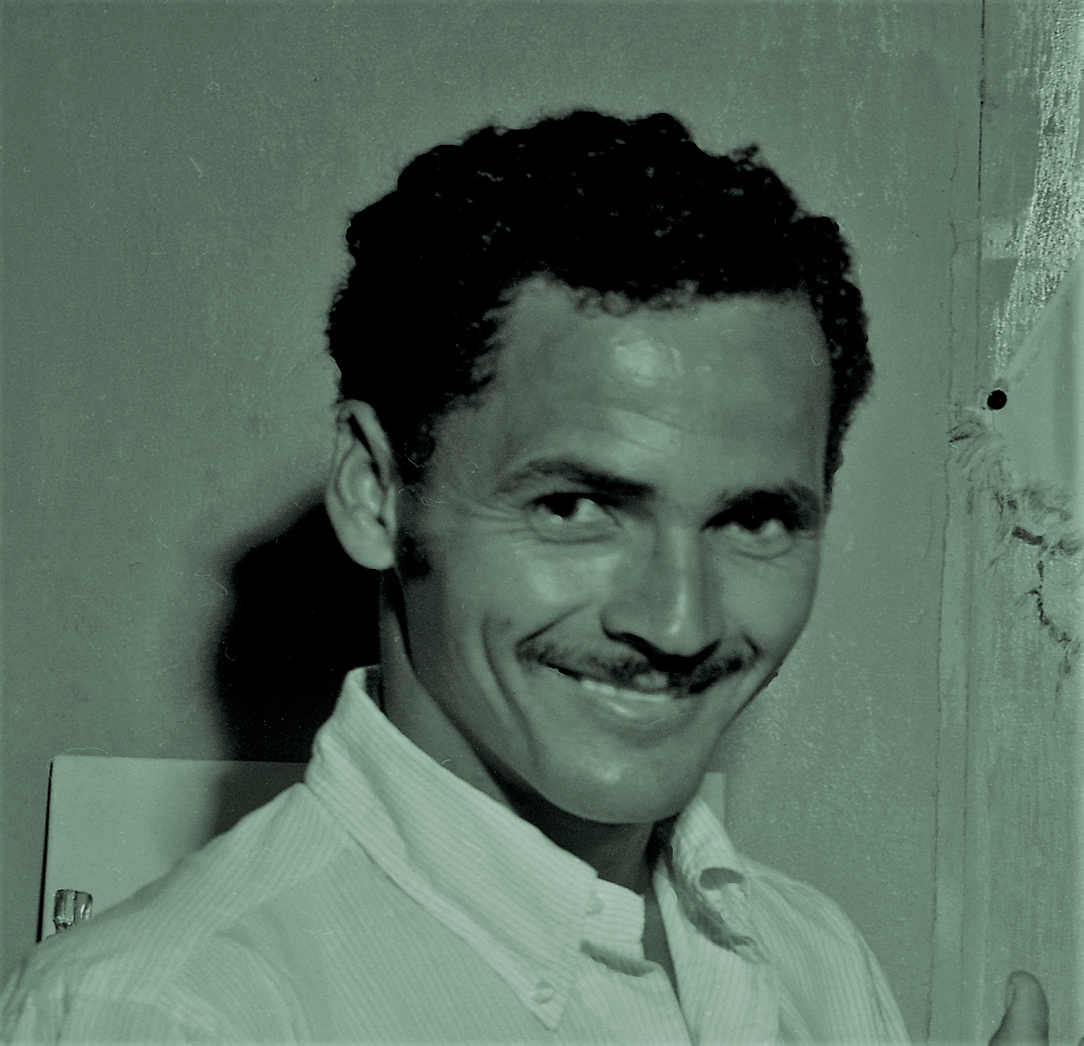

James Ronald Webster

March 2, 1926- December 9, 2016

Father of the Nation, 1st Chief Minister of Anguilla, Revolutionary Leader

James Ronald Webster: A Revolutionary for the People

Don E. Walicek

University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus

Mr. James Ronald Webster is often remembered today as the protagonist of the Anguilla Revolution. One reason for this is that many consider him to have demonstrated the prototypical features of a hero: bravery, sacrifice, conviction, risk-taking, and moral integrity for an honorable purpose. But today, 50 years after the people of the island first rejected its inclusion in the Associated State of St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla, it’s clear that Webster’s influence has extended into a much wider realm. His example has assisted in the preservation and propagation of one of Anguilla’s most valuable resources, a strong collective identity. In this manner, he, like other national heroes, still impacts how people mold and interpret the world. He does so through contemporary political realities often taken for granted, through memories and passed down through the generations, and through narratives that are put to the page to become history.

James Ronald Webster was born in the village of Island Harbour on 2 March 1926. He was one of the 8 surviving children of the 16 born to Mary Octavia Webster, a homemaker and seamstress, and Robert Livingstone Webster, a fisherman. Webster’s father traveled the “Santo Domingo Trail,” a pattern of seasonal migration that took most of the British colony’s able-bodied men to work on the sugarcane estates of Hispaniola for several months each year.

Webster studied in Anguilla’s East End School as a young boy, but due to hard economic times and limited opportunities locally, he had to end his formal education early. At the age of 10, he and 2 siblings migrated the short distance to the neighboring Dutch colony of St. Maarten. Though mere children, they labored to sustain themselves and send money home. Webster found employment at Mary Fancy’s Estate in Cul-de-Sac, where he looked after large numbers of livestock and delivered fresh milk by donkey. His supervisors, D. C. van Romondt, its Dutch owner, and Josephine Edwards, an Anguilla-born Kittian, treated Webster well, and by his early twenties he felt as if he were an adopted son.

He worked on the estate for more than two decades, and in 1958, at age 32, he inherited van Romondt’s property, then valued at approximately US$1.5 million (Webster, 2011). This inheritance was not the only thing that informed his vision of the future. Webster witnessed dramatic improvements in the standard of living there in St. Maarten. He also observed the growth of a fledgling tourist industry and learned about financial assistance programs offered by Dutch and French colonial administrators. These experiences contributed to his entrepreneurial spirit and his eventual emergence as a key leader of his island’s people.

Webster returned to Anguilla in 1964, hopeful about the prospects of economic and social development. The island still lacked basic industry, paved roads, electrical service, modern plumbing, a telephone system, and an adequate port. He encouraged improvements and garnered local support for their implementation, but authorities in St. Kitts did not support these initiatives. He was perplexed and frustrated when they rejected his plans to use local volunteers to build roads and extend electrical service. Identifying Anguilla’s political status as central to its problems, Webster charged that St. Kitts administrators constituted a dictatorial regime bent on keeping the island subservient.

A deeply religious man, Webster’s faith contributed to his emergence as a vocal and determined political leader. He attributed his political activism to nothing other than divine intervention, years later recalling, “As I lay in bed one night pondering the plight of Anguilla, I heard the call to lead the people of Anguilla” (Webster, 2011). In 1964 this vision led him to become a member of the People’s Action Movement (PAM), the St. Kitts-based opposition party established to promote inter-island solidarity, employment opportunities, and economic development.

Webster’s political commitment was emboldened in February 1967, when a substantial number of Anguillians put their personal safety at risk in a push for political change. They interrupted and shut down the controversial “queen show” associated with the pro-statehood cause (i.e., continued union with St. Kitts and Nevis). Tensions flared thereafter, and within a few months the rebels had forced the Kittian constabulary off the island, with their arms and ammunition being confiscated.

Later that year, Webster was instrumental in closing the airport and establishing beach patrols in order to maintain stability and prevent any invasion by St. Kitts. Some of his arguments had anti-colonial elements. For example, Webster cautioned that the building of even one huge Hilton-like hotel would convert the island into “a nation of bus boys, waiters, and servants.” He also critiqued the example of St. Thomas, where locals had become “second class citizens and had to run from their own country” (Webster interview, 2014).

Webster and the journalist Atlin Harrigan were among the men linked to these developments and soon emerged as the two most important leaders of the movement that today is remembered as the Anguilla Revolution. They would later divide on the issue of whether Anguilla should become a fully sovereign state, which Webster at the time argued for, or maintain a link with British rule, which Harrigan advocated.

Webster played an important role in the Barbados Conference, a meeting in July of that year attended by representatives of Anguilla, British diplomats, and Caribbean Commonwealth officials. When they faced threats that regional troops would be used to maintain the territorial integrity of the Associated State of St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, some of Anguilla’s representatives signed an agreement endorsing a return to St. Kitts, but Webster refused to do so. Others in attendance report that he defiantly tossed the agreement across the negotiation table.

In addition, Webster served three times as the chief executive and chairman of the Anguilla Council, the body responsible for peacekeeping and local government during the crisis. In these positions he organized meetings with local supporters, collaborated with lawyers and consultants, strategically courted the international press, and spearheaded initiatives to support the movement. Among the latter were requests for financial backing from international agencies, the issuing of stamps, and the sale of honorary passports to supporters of the cause. He also pleaded Anguilla’s case abroad, speaking in London before British government officials and in New York City at the United Nations.

In February 1969, when Anguilla adopted a new constitution making it an independent republic, Webster was declared president of the Republic of Anguilla. As head of state of the world’s smallest and youngest country, he reiterated three demands: a complete break with St. Kitts, internal self-government, and long-term direct association with Britain.

When 330 paratroopers and marines invaded Anguilla on March 19, 1969, Webster was ready. The previous day, Webster had received word that “the British were coming” from allies in Antigua, and he did what he could to “prepare the people and avoid bloodshed.” Early the morning of the invasion he drove to the secondary school where hundreds of supporters lifted him up in the air before he turned himself in. When British officers interrogated him and asked to turn over his weapons, he argued that he was innocent of any crime. In Webster’s words, “All that I could explain to those who cross-questioned me was that I was carrying out the wishes of my people. I had a duty to protect my country and its people” (Webster interview, 2014).

During the subsequent period of British occupation, colonial officers closely monitored him. They believed he was willing to become a martyr for the cause. For this reason they worked behind the scenes to exacerbate his conflicts with political opponents and reduce his political influence within the local population. Webster was sometimes criticized for what could appear to be a heavy-handed style of decision-making, but even his political opponents would respect him for his foresight and the perseverance with which he pursued the goals of the revolution over a period of fourteen years.

Webster twice served as Anguilla’s chief minister (1976–1977 and 1980–1984). While his first term ended with a controversy, but in 1980 he pushed for Anguilla’s formal separation from St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla as part of his campaign and was re-elected. The island lived up to its motto of “strength and endurance” under Webster’s leadership. In December of 1980, the island was formally separated from the Associated State of St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla and recognized as a Crown Colony (later referred to with the term “dependent territory” and thereafter “overseas territory”). Webster celebrated the long-awaited event as the end of oppression as well as a new opportunity for regional cooperation (Webster, 2011). The following year he led a delegation to London for talks that resulted in the approval of a new constitution. Another noteworthy accomplishment is his introduction of a social security system in 1982.

In 2010, Webster’s birthday, 2 March, became one of Anguilla’s official public holidays. Three years later he formally requested that the various commemorative activities associated with the holiday be discontinued, citing high costs and their proximity to Anguilla Day celebrations on 30 May. His statement to the press underscored his gratitude for the recognition he received and the wish that his birthday continue to be listed an official holiday. It also voiced disappointment that the day had become a source of political rivalry and disunity.

Insisting that memory should enrich people’s lives through loyalty to the truth and and a useful sense of direction, Webster rejected the idea that he was or should be remembered as the main protagonist in the battle to resolve Anguilla’s political status. In his words, “Although I am being celebrated as ‘The Father of the Nation’ and the ‘Leader of the Anguilla Revolution,’ the Revolution was not about me. It was for the freedom and prosperity of the people of Anguilla: those who lived during that period; those who are still alive today; and those of our generations yet unborn” (The Anguillian, 18 January 2013).

Bibliography

Dyde, Brian. Out of the Crowded Vagueness: A History of the Islands of St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla. Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean, 2005.

Petty, Colville L. and A. Nat Hodge. Anguilla’s Battle for Freedom, 1967-1969. The Valley, Anguilla: PETNAT, 2010.

J. Ronald Webster, interview by D.E. Walicek, February 17, 2014, transcript.

“Ronald Webster Withdraws from Official Birthday Celebrations.” The Anguillian, 18 January 2013.

Webster, J. Ronald. Revolutionary Leader: Reflections on Life, Leadership, Politics. Denver: Outskirts Press, 2011.

Don E. Walicek

University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus

Mr. James Ronald Webster is often remembered today as the protagonist of the Anguilla Revolution. One reason for this is that many consider him to have demonstrated the prototypical features of a hero: bravery, sacrifice, conviction, risk-taking, and moral integrity for an honorable purpose. But today, 50 years after the people of the island first rejected its inclusion in the Associated State of St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla, it’s clear that Webster’s influence has extended into a much wider realm. His example has assisted in the preservation and propagation of one of Anguilla’s most valuable resources, a strong collective identity. In this manner, he, like other national heroes, still impacts how people mold and interpret the world. He does so through contemporary political realities often taken for granted, through memories and passed down through the generations, and through narratives that are put to the page to become history.

James Ronald Webster was born in the village of Island Harbour on 2 March 1926. He was one of the 8 surviving children of the 16 born to Mary Octavia Webster, a homemaker and seamstress, and Robert Livingstone Webster, a fisherman. Webster’s father traveled the “Santo Domingo Trail,” a pattern of seasonal migration that took most of the British colony’s able-bodied men to work on the sugarcane estates of Hispaniola for several months each year.

Webster studied in Anguilla’s East End School as a young boy, but due to hard economic times and limited opportunities locally, he had to end his formal education early. At the age of 10, he and 2 siblings migrated the short distance to the neighboring Dutch colony of St. Maarten. Though mere children, they labored to sustain themselves and send money home. Webster found employment at Mary Fancy’s Estate in Cul-de-Sac, where he looked after large numbers of livestock and delivered fresh milk by donkey. His supervisors, D. C. van Romondt, its Dutch owner, and Josephine Edwards, an Anguilla-born Kittian, treated Webster well, and by his early twenties he felt as if he were an adopted son.

He worked on the estate for more than two decades, and in 1958, at age 32, he inherited van Romondt’s property, then valued at approximately US$1.5 million (Webster, 2011). This inheritance was not the only thing that informed his vision of the future. Webster witnessed dramatic improvements in the standard of living there in St. Maarten. He also observed the growth of a fledgling tourist industry and learned about financial assistance programs offered by Dutch and French colonial administrators. These experiences contributed to his entrepreneurial spirit and his eventual emergence as a key leader of his island’s people.

Webster returned to Anguilla in 1964, hopeful about the prospects of economic and social development. The island still lacked basic industry, paved roads, electrical service, modern plumbing, a telephone system, and an adequate port. He encouraged improvements and garnered local support for their implementation, but authorities in St. Kitts did not support these initiatives. He was perplexed and frustrated when they rejected his plans to use local volunteers to build roads and extend electrical service. Identifying Anguilla’s political status as central to its problems, Webster charged that St. Kitts administrators constituted a dictatorial regime bent on keeping the island subservient.

A deeply religious man, Webster’s faith contributed to his emergence as a vocal and determined political leader. He attributed his political activism to nothing other than divine intervention, years later recalling, “As I lay in bed one night pondering the plight of Anguilla, I heard the call to lead the people of Anguilla” (Webster, 2011). In 1964 this vision led him to become a member of the People’s Action Movement (PAM), the St. Kitts-based opposition party established to promote inter-island solidarity, employment opportunities, and economic development.

Webster’s political commitment was emboldened in February 1967, when a substantial number of Anguillians put their personal safety at risk in a push for political change. They interrupted and shut down the controversial “queen show” associated with the pro-statehood cause (i.e., continued union with St. Kitts and Nevis). Tensions flared thereafter, and within a few months the rebels had forced the Kittian constabulary off the island, with their arms and ammunition being confiscated.

Later that year, Webster was instrumental in closing the airport and establishing beach patrols in order to maintain stability and prevent any invasion by St. Kitts. Some of his arguments had anti-colonial elements. For example, Webster cautioned that the building of even one huge Hilton-like hotel would convert the island into “a nation of bus boys, waiters, and servants.” He also critiqued the example of St. Thomas, where locals had become “second class citizens and had to run from their own country” (Webster interview, 2014).

Webster and the journalist Atlin Harrigan were among the men linked to these developments and soon emerged as the two most important leaders of the movement that today is remembered as the Anguilla Revolution. They would later divide on the issue of whether Anguilla should become a fully sovereign state, which Webster at the time argued for, or maintain a link with British rule, which Harrigan advocated.

Webster played an important role in the Barbados Conference, a meeting in July of that year attended by representatives of Anguilla, British diplomats, and Caribbean Commonwealth officials. When they faced threats that regional troops would be used to maintain the territorial integrity of the Associated State of St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, some of Anguilla’s representatives signed an agreement endorsing a return to St. Kitts, but Webster refused to do so. Others in attendance report that he defiantly tossed the agreement across the negotiation table.

In addition, Webster served three times as the chief executive and chairman of the Anguilla Council, the body responsible for peacekeeping and local government during the crisis. In these positions he organized meetings with local supporters, collaborated with lawyers and consultants, strategically courted the international press, and spearheaded initiatives to support the movement. Among the latter were requests for financial backing from international agencies, the issuing of stamps, and the sale of honorary passports to supporters of the cause. He also pleaded Anguilla’s case abroad, speaking in London before British government officials and in New York City at the United Nations.

In February 1969, when Anguilla adopted a new constitution making it an independent republic, Webster was declared president of the Republic of Anguilla. As head of state of the world’s smallest and youngest country, he reiterated three demands: a complete break with St. Kitts, internal self-government, and long-term direct association with Britain.

When 330 paratroopers and marines invaded Anguilla on March 19, 1969, Webster was ready. The previous day, Webster had received word that “the British were coming” from allies in Antigua, and he did what he could to “prepare the people and avoid bloodshed.” Early the morning of the invasion he drove to the secondary school where hundreds of supporters lifted him up in the air before he turned himself in. When British officers interrogated him and asked to turn over his weapons, he argued that he was innocent of any crime. In Webster’s words, “All that I could explain to those who cross-questioned me was that I was carrying out the wishes of my people. I had a duty to protect my country and its people” (Webster interview, 2014).

During the subsequent period of British occupation, colonial officers closely monitored him. They believed he was willing to become a martyr for the cause. For this reason they worked behind the scenes to exacerbate his conflicts with political opponents and reduce his political influence within the local population. Webster was sometimes criticized for what could appear to be a heavy-handed style of decision-making, but even his political opponents would respect him for his foresight and the perseverance with which he pursued the goals of the revolution over a period of fourteen years.

Webster twice served as Anguilla’s chief minister (1976–1977 and 1980–1984). While his first term ended with a controversy, but in 1980 he pushed for Anguilla’s formal separation from St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla as part of his campaign and was re-elected. The island lived up to its motto of “strength and endurance” under Webster’s leadership. In December of 1980, the island was formally separated from the Associated State of St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla and recognized as a Crown Colony (later referred to with the term “dependent territory” and thereafter “overseas territory”). Webster celebrated the long-awaited event as the end of oppression as well as a new opportunity for regional cooperation (Webster, 2011). The following year he led a delegation to London for talks that resulted in the approval of a new constitution. Another noteworthy accomplishment is his introduction of a social security system in 1982.

In 2010, Webster’s birthday, 2 March, became one of Anguilla’s official public holidays. Three years later he formally requested that the various commemorative activities associated with the holiday be discontinued, citing high costs and their proximity to Anguilla Day celebrations on 30 May. His statement to the press underscored his gratitude for the recognition he received and the wish that his birthday continue to be listed an official holiday. It also voiced disappointment that the day had become a source of political rivalry and disunity.

Insisting that memory should enrich people’s lives through loyalty to the truth and and a useful sense of direction, Webster rejected the idea that he was or should be remembered as the main protagonist in the battle to resolve Anguilla’s political status. In his words, “Although I am being celebrated as ‘The Father of the Nation’ and the ‘Leader of the Anguilla Revolution,’ the Revolution was not about me. It was for the freedom and prosperity of the people of Anguilla: those who lived during that period; those who are still alive today; and those of our generations yet unborn” (The Anguillian, 18 January 2013).

Bibliography

Dyde, Brian. Out of the Crowded Vagueness: A History of the Islands of St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla. Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean, 2005.

Petty, Colville L. and A. Nat Hodge. Anguilla’s Battle for Freedom, 1967-1969. The Valley, Anguilla: PETNAT, 2010.

J. Ronald Webster, interview by D.E. Walicek, February 17, 2014, transcript.

“Ronald Webster Withdraws from Official Birthday Celebrations.” The Anguillian, 18 January 2013.

Webster, J. Ronald. Revolutionary Leader: Reflections on Life, Leadership, Politics. Denver: Outskirts Press, 2011.

Edison L Hughes

|

Albena Lake Hodge

|

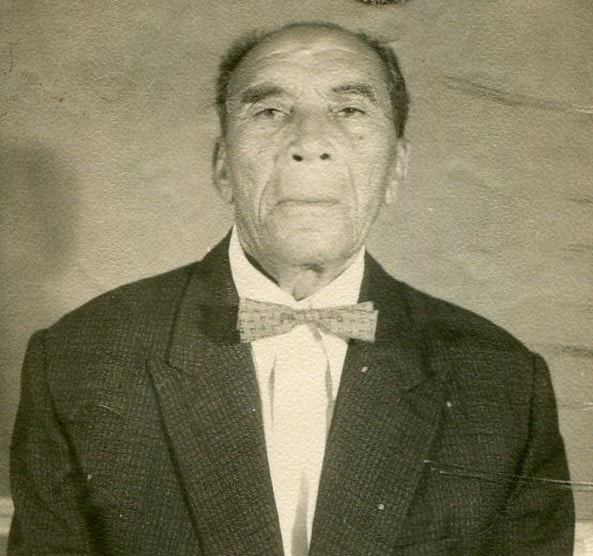

Atlin Naralda Harrigan

1939- 2005

Revolutionary Leader, Founder of The Beacon, Former Speaker of the House

leader of the Anguilla Revolution, editor and founder of The Beacon, and Speaker of the Anguilla House of Assembly, was born in Island Harbour, Anguilla on December 8, 1939. The fourth of ten children, his parents were Mary Alberta Webster, a homemaker, and Fredrick Osborne Harrigan, a fisherman, businessman, and highly respected community leader.

As a young boy Harrigan studied at the Old East End School. At the time secondary education was not available on the island. in 1960 he migrated to the United Kingdom and trained as an electrician. Around this time he married Mona Hunte- Harrigan, a union to which two children would be born. Approximately two years later he returned to the Caribbean and began working at the Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority in St. Thomas.

Harrigan's experiences abroad contributed to his awareness that Anguilla lagged behind other Caribbean islands in terms of even its most basic infrastructure. From the Virgin Islands he worked to establish an association that would contribute to development projects in Anguilla, principally those that would provide roads, medical services, and modern systems of electricity and running water. He also wrote regularly for one of the main papers of St. Kitts, The Democrat. Harrigan's publication of confidential minutes from the St. Kitts legislature in the paper in 1967 helped to mobilize widespread opposition to Anguilla's inclusion in the Associated State of St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla. He was one of the first to charge that statehood was a highly problematic and unjust constitutional arrangement that both guaranteed Kittian domination and thwarted political and economic progress in Anguilla.

Harrigan was part of the small inner circle to lead the Anguilla Revolution. Local historians Nat A. Hodge and Colville Petty refer to him as one of its "principal planners and strategists," pointing out that he "was no armchair leader" but someone "in the trenches with the foot soldiers" (200). In 1967, he joined the public protest that shut down the controversial pro statehood queen show and secretly transported arms used to expel the Kittian constabulary from the island. He also captained the boat that took men to St. Kitts in an attempt to take control of the island, overthrow its government, and kidnap Premiere Robert L. Bradshaw. He was instrumental in actions that put the island on a path to self-determination.

In the early months of the revolution, Harrigan generally saw eye to eye with the leader of the movement, Ronald Webster. In fact, years later both would fondly remember the many days they spent together when they hid from police in Anguilla's scant bush. The substantial tensions that later arose between Harrigan and Webster concern two main issues. First, Harrigan advocated that the island should "stay colonial" and insisted that it was Britain's duty to severe Anguilla's administrative and political ties with St. Kitts. He pushed for direct relations with London and adamantly rejected the more radical option of full independence backed by Webster and his supporters. For Harrigan, independence was amputation, a serious operation "only to be taken at the last resort if all other methods of saving the limb should have failed" (Petty and Hodge, 1997: 201). Second, Harrigan insisted that discussion and debate were essential for local government, staunchly critiquing Webster's authoritarian and unilateral decision-making style. Harrigan suffered retaliation for expressing his critiques. Opponents confiscated the press of The Beacon, Anguilla's first newspaper, which he had founded in 1967 and also repeatedly painted him as an enemy of the movement.

Nevertheless, Harrigan remained active in shaping Anguilla's political landscape. He sat on the Anguilla Council from 1968 to 1972 and led the Anguilla Constructive Democratic Movement, the opposition party that he founded in April 1969. In the late 1970's, he served on the Legislative Council and in 1985 became Speaker of the Anguilla House of Assembly, a position he held for nine years. In 1992 Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II appointed Harrigan Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

Even after Anguilla's was finally recognized as a British Dependent Territory in 1980, Harrigan rejected the idea that Anguilla's population should eventually seek independence. In his words, We have achieved what we wanted. On the question of independence, there is no such thing, though countries may have separate laws, constitutions, flags, anthems or currency. The truth is one cannot survive without the other regardless of wealth or size" (Harrigan 1997).

Anguilla's first state funeral was held in tribute to Harrigan in 2005. Two years later, in conjunction with the Anguilla Revolution's 40th anniversary, Harrigan was honored with a commemorative postage stamp.

Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro-Latin Anerican Biography

Editor-in-chief: Franklin W. Knight and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Don E. Walicek, University of Puerto Rico

Bibliography

Harrigan, Atlin N. Revolution was Rumbling Like a Volcano." Presentation at Anguilla Day Celebration. Archives of the Anguilla Library Service's Heritage Room, 1997.

Petty, Colville and A. Nat Hodge. Anguilla's Battle for Freedom, 19671969. The Valley, Anguilla: PETNAT Co., Ltd., 2010.

Edwin Wallace Rey

|