WelcomeWelcome to the website of the Anguilla Archaeological and Historical Society (AAHS).

This is the premier organisation committed to protecting, preserving and promoting the national treasures of Anguilla’s heritage. We explore connections between Anguilla’s past and present through research, advocacy, documentation, networking and collections of rare and irreplaceable items. |

Traditional Boat Race - Meads Bay, Anguilla 1969

|

Our Past

|

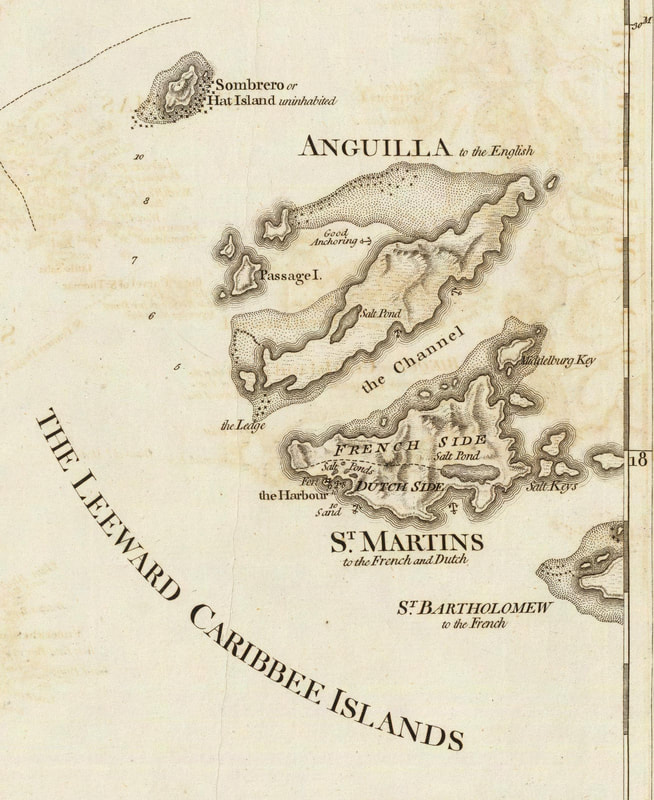

Shell Mask by AAHS on Sketchfab Brief History of Anguilla

Anguilla was inhabited by Amerindians back to about 4,000 years ago. They are now commonly referred to as the Arawaks. They had arrived coming up the chain of islands from South America. Much of their interesting pottery is still to be found and has been unearthed in ongoing although infrequent archaeological digs. In the mid sixteen hundreds British settlers arrived but the Arawaks were gone from Anguilla by then. A further French invasion occurred in 1666. Those first colonial settlers found the Island to be a harsh environment from which to make a sustainable way of life. The cotton crops became redundant and in the early years of the seventeen hundreds, sugar had replaced cotton as being a more lucrative crop. Of course, labour was badly needed for this to happen and African slaves were brought to Anguilla and finally outnumbered the original European settlers. Attacks by the French in the eighteen hundreds, due to conflicts in Europe, were all repelled but British Government influence initiated a union between Anguilla and St. Kitts in 1825. This was distinctly disadvantageous to Anguilla and its inhabitants eking out a living from the rocky landscape and were experiencing regular droughts causing further hardship. Although Anguillians were given the British backed opportunity to emigrate to Guiana, most opted to stay and became fishermen and farmers but the hardship continued due to the frequent droughts and by the beginning of the 20th Century many Anguillians ended up cutting cane in Santo Domingo. Constitutional change in 1956 resulted in St. Kitts, Nevis and Anguilla being recognized as one colonial entity. Anguillians were no better pleased with this relationship than they had been over one hundred years earlier and in 1967 the discontent sparked off the Revolution. Anguillian's felt powerless and deprived under the then arrangement with St.Kitts, forced upon them and expressed their wish to secede and be governed directly from the United Kingdom. Following a second plebiscite in 1969, all negotiations having broken down, Anguilla declared itself an Independent Republic. After an interim period in which British proposals for a solution to the dissatisfaction failed, on 19th March 1969 four hundred British troops invaded Anguilla and a Commissioner was appointed to govern the Island. On 19th December 1980, Anguilla was recognized as a separate British Dependent Territory having its own new constitution in 1982. However further amendments continued and by 1990, Anguilla finally became the country we know today as that of a British Overseas Territory. Archaeological digs continue to uncover remnants of Anguilla’s interesting history. Read more About Anguilla |

Anguilla's Giant Rodent (Amblyrhiza Inundata)

Some Islands in the Caribbean have not only goats and sheep, but also, in the wild, monkeys, donkeys, parrots and even alligators. Here on Anguilla, at the present time, we are limited to goats, sheep and a variety of reptiles plus on the domesticated side, cattle, pigs, donkeys and some horses. Nothing particularly exotic or different.

It has been reported that many years ago, when the island had more vegetation, there were alligators here in some of the ponds and swamps on Anguilla. But beyond that more unusual creature, for many centuries previously, giant rodents about the size of black bears roamed the island. { Donald A. McFarland} The presence of these unusual animals on Anguilla is analyzed in detail in the following report by Dr. McFarland in 1991. Read More.

It has been reported that many years ago, when the island had more vegetation, there were alligators here in some of the ponds and swamps on Anguilla. But beyond that more unusual creature, for many centuries previously, giant rodents about the size of black bears roamed the island. { Donald A. McFarland} The presence of these unusual animals on Anguilla is analyzed in detail in the following report by Dr. McFarland in 1991. Read More.

Click here Additional Reading on Anguilla's Giant Rat

Captain Kidd and his Anguilla Connection

|

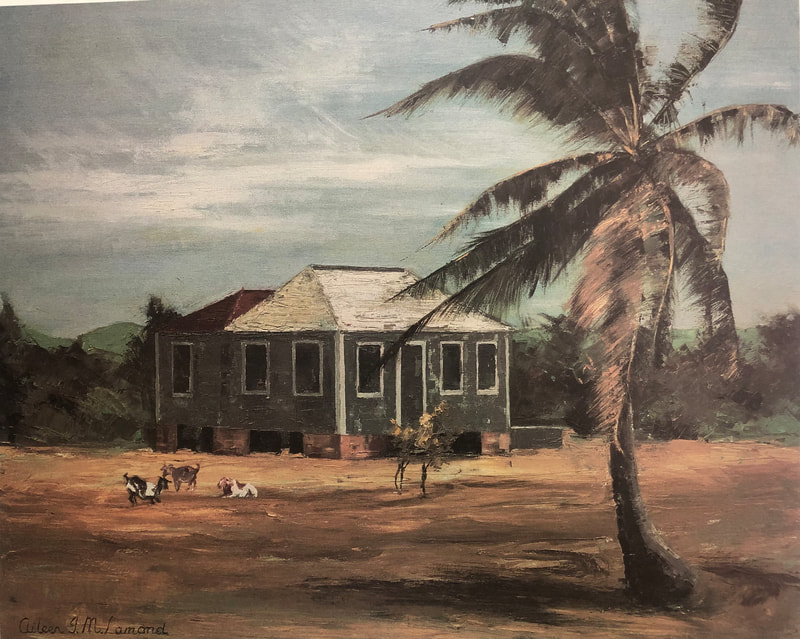

Historic Houses

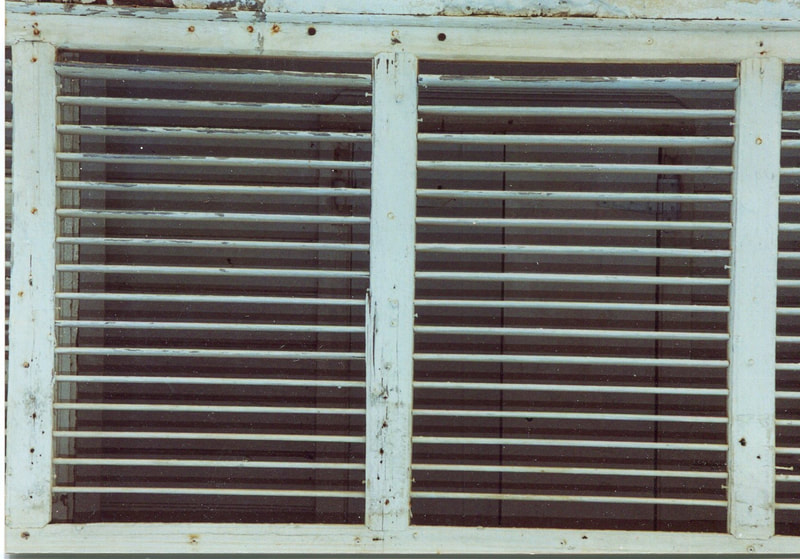

Old Court HouseThe ruins of the old Courthouse and Jail, located at the top of the highest point of Anguilla -Crocus Hill, commands a specular view of most of Anguilla and the surrounding Islands. All that remains of this once prominent building is the stone basement, constructed in the eighteenth century and used as a powder magazine for storing weapons and explosives. It was later converted into a prison, apparently not a very secure one, as in 1831, three men under sentence of death managed to escape by cutting a hole in the roof.

Hurricane Alice destroyed the old courthouse in 1955, although the small cells and a stone - walled enclosure, topped with the broken bottles are still intact. The wooden upper floor that once housed the Court, Treasury, Post office and Customs offices was destroyed. UPDATE . We are so happy to be leading the historical renovation of this treasured building. New museum location coming 2022 . Learn more about the restoration. |

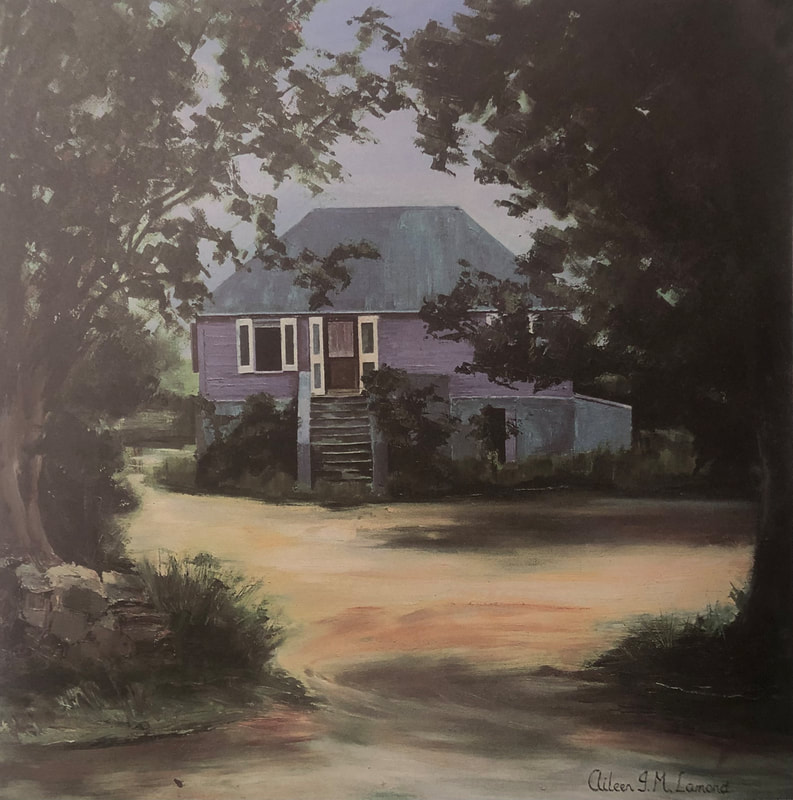

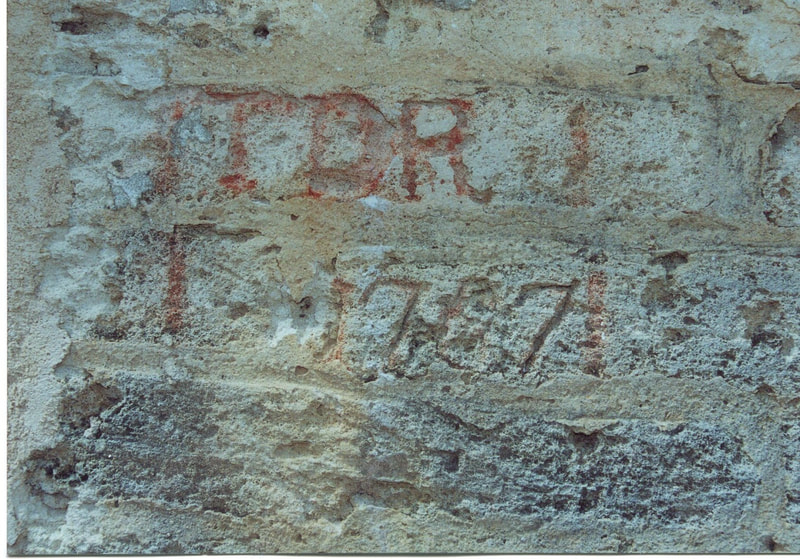

Warden's PlaceThis Beautiful 18th Century Plantation House, Originally constructed in the 1700's as a sugar and cotton plantation building, is a historically important stone and wood treasure. Known as the "Warden's Place" was built by slave labour for a Dutch family from St. Maarten and was part of an estate whose acreage extended to Crocus Bay.

Emancipation of the slaves in the 1800s, Combined with years of drought and famine resulted in abandonment by the plantation owners. Eventually, the descendants of the slaves who originally tilled the land purchased the forsaken property and land. The British government leased it as a residence for the medical doctor assigned to Anguilla by the British in the early 1900s. The Doctor, who also doubled as the Magistrate and the Chief of Police, as well asas many later British Agents for the Crown, resided here into the 1950s, this led to the estate becoming known as the Warden’s Place. The first floor is made of stone from Limestone Bay and the upper floor of wood. The rock oven is still in use today. |

Video showing some traditional houses of Anguilla 1969

Many of which has been lost through the years.

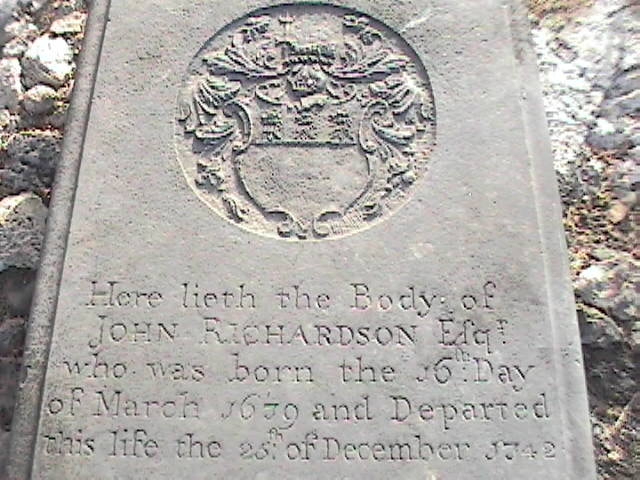

Governor Richardson’s Grave

In a quiet secluded corner, under an beautiful old Lignum Vitae tree in Sandy Hill Cemetery, a very old grave can be found, commonly referred to as Governor Richardson’s Grave.

About fifteen years ago, the Anguilla Archaeological and Historical Society restored this piece of history by cleaning around the site and with much muscle power manoeuvered the large slab, of dark grey slate back into place over the actual grave. A protective iron fence was installed, completely surrounding the slab and an information plaque attached where the grave could be best viewed.

It is believed that the heavy, substantial slate tablet, now unfortunately slightly damaged at one corner through neglect, was brought from Wales, already engraved for the burial site of John Richardson.

On it, you can still clearly read “Here leith the Body of John Richardson Esq. who was born the 6th Day of March 1679 and Departed this life the 25th of December 1742”.

Above the inscription, within a circle, is a display of heraldry. A member of the Society visited various public offices in London in an effort to learn more about Mr Richardson than is currently known on the Island, but the efforts drew a blank. However, at the College of Arms, an official known as a Herald was able to explain that gauntlet recognized on the grave stone was a ‘dexter arm in armour fesswise holding in a hand an indeterminate object which may be a trident or a broken sword. No recognition of a Crest of this precise design on the grave slab has been determined to be directly connected to any particular Richardson family.

So the mystery remains entombed in its shady resting place for one and all to visit.

In a quiet secluded corner, under an beautiful old Lignum Vitae tree in Sandy Hill Cemetery, a very old grave can be found, commonly referred to as Governor Richardson’s Grave.

About fifteen years ago, the Anguilla Archaeological and Historical Society restored this piece of history by cleaning around the site and with much muscle power manoeuvered the large slab, of dark grey slate back into place over the actual grave. A protective iron fence was installed, completely surrounding the slab and an information plaque attached where the grave could be best viewed.

It is believed that the heavy, substantial slate tablet, now unfortunately slightly damaged at one corner through neglect, was brought from Wales, already engraved for the burial site of John Richardson.

On it, you can still clearly read “Here leith the Body of John Richardson Esq. who was born the 6th Day of March 1679 and Departed this life the 25th of December 1742”.

Above the inscription, within a circle, is a display of heraldry. A member of the Society visited various public offices in London in an effort to learn more about Mr Richardson than is currently known on the Island, but the efforts drew a blank. However, at the College of Arms, an official known as a Herald was able to explain that gauntlet recognized on the grave stone was a ‘dexter arm in armour fesswise holding in a hand an indeterminate object which may be a trident or a broken sword. No recognition of a Crest of this precise design on the grave slab has been determined to be directly connected to any particular Richardson family.

So the mystery remains entombed in its shady resting place for one and all to visit.

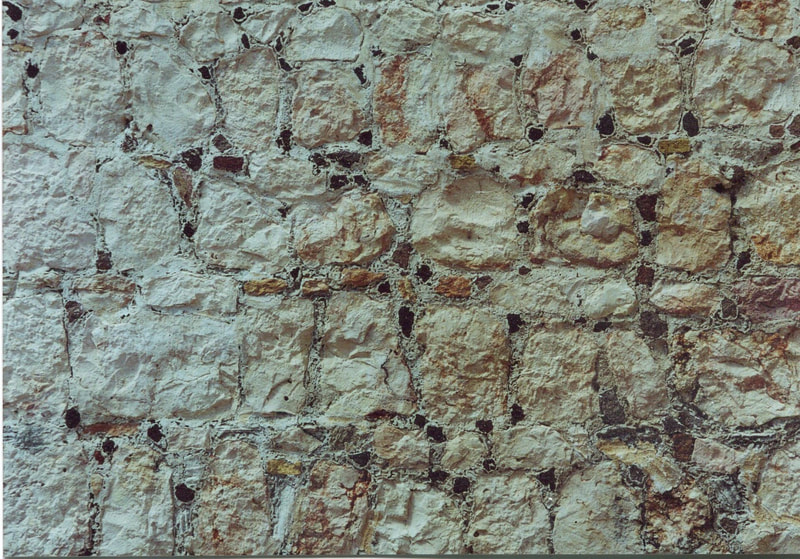

Scenes from Warden's Place

The Ruins

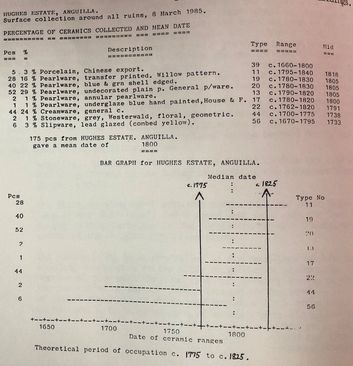

Plantation Hughes EstateA Study of Ceramic Sherds from Hughes Estate

by Desmond Nicholson The Antigua Archaeological and Historical Society On 8th March 1985 while visiting Anguilla at the invitation of the Anguilla Archaeological and Historical Society, a brief trip was made to the ruins at Hughes Estate, next to Skiffles resort on South Hill. A quantity of ceramic sherds from the historical period were collected and analysed according to generally accepted methods with the intention of establishing a theoretical period of occupation of this site. Since we know the precise dates when each different type of ceramic was manufactured, it is an easy task to establish a likely time for their introduction into estates in the West Indies. Analysis of the Hughes Estate sherds reveals a theoretical period of occupancy of 1775-1825, with a median date of circa 1800. This appears to confirm with what little we know about this site and is supported by the architectural and structural evidence of the buildings. |

Benzies Plantation Ruins Typical Anguillian boiling house, animal round, and curing house of the eighteenth century can still be seen in the ruins at Benzies, over the Shannon Hill on the north coast . Who Benzie was is not now known. The ruins of the boiling house and curing house at Benzies lie overgrown with trees and scrub, in a sad state of disrepair, almost on the beach.

They are very small in comparison to the ruins of the other sugar islands. They were not in use for any long period. We do not know if this small, abandoned factory ever made any sugar. We do not know who owned it. ‘Benzies’ is more accurately the name of a nearby bay, used for swimming years ago by the residents of North Hill. |

The Ocean

Sombrero Island" Here, exposed to all the extremes of the elements, neighbourless, it is intended forever to be a way station for Time. Here, there have occurred many changes and no change. This rock island is the center of the world for the .....men who maintain the Sombrero lighthouse."

Read More. Voyage to Sombrero via

Anguilla's Famous Vessel The Warspite, 1969 |

El Buen ConsejoWith the Spanish colonization of newly discovered lands in Mexico and South America beginning in the 16th Century, an ever-increasing amount of treasure and trade goods began to flow across the Atlantic Ocean. Exotic trade goods from the Far East and treasure from mines in South and Central America were being shipped back to Spain while European-made products occupied the holds of these vessels on their voyages to New World. Rival European nations as well as privateers and pirates would attempt to seize these richly laden vessels whenever possible. To counter this threat, Spain devised a convoy system whereby merchant vessels sailed along with heavily armed galleons for protection. A group of vessels crossing the ocean in this manner were referred to a flotilla. For almost 200 years, the vast sums of gold and silver her colonies provided, coupled with her long history of naval and military traditions, made Spain the strongest military power in the world.

Read More |

The Warspite Built in 1909 in Sandy ground and originally christened the Gazelle. This 40 ton Vessel was bought in 1916 by Arthur Romney and renamed the Warspite. Mr. Romney made a couple of alterations to the bow section extending her length by 11 feet . Known locally as a fast ship , she famously sailed between Anguilla and Santo Domingo transporting Anguillian men to work on the Cane fields. Throughout the 40s-70s she transported goods throughout the Caribbean especially salt to Trinidad and Tobago as well as her bi-weekly trips to the lighthouse at Sombrero.

Later on in her life The Warspite was motorized , keeping up with the times. Tragically, during Hurricane Klaus in 1984, the Warspite was cast ashore and destroyed. Learn More |

© Claire E Devener © Claire E Devener

The History of Boat Racing in Anguilla by David Carty If the sport of Kings ever existed in Anguilla this generation is certainly ignorant of what it must have been like. Perhaps Carter Rey, now long dead, was the first man to race a horse somewhere around Wallblake. But every Anguillian in the past and today has seen a boat race and indeed this indigenous sport is not too much unlike the sport of Kings in many ways.

It has never ceased to impress me how unique boat racing is in Anguilla; how each boat at once exudes a quality of both grace and wildness; how the racers and the fans endow each boat with a definite personality; and of course how the spectators ashore win and lose, at times substantially, on bets made on every race. Read More |

"It’s death of whelks mek soldier crab get shell."Local Proverb

Scenes of Wallblake House

"As sure as Moses strike de rock and water fly from it". Local Saying

Past Industries

The Salt Industry of Anguilla |

Tobacco, Cotton, Salt and

|

Fishing & Sailing

|

Naturally the history of Anguilla is closely tied to the sea. Fishing and boat building have always been of enormous importance to the survival of its people.

Because of the low rainfall in Anguilla and the lack of abundant rich soil, the sugar plantations which were set up in the eighteenth century did not survive economically. In commercial agriculture, the social ramifications of these developments for the people of Anguilla were far reaching. Anguillians were forced either to immigrate to other islands to obtain work or seek livelihoods on the sea, through fishing and shipping. Both alternatives brought the island’s men-folk directly to the sea, although obviously those who emigrated for work, returning home periodically, had less of a relationship with the sea than those who chose to fish or handle shipping. The latter group was divided roughly into two segments: those who fished, mostly in small boats, and those who traded throughout the Caribbean Islands on schooners. Today’s racing sailboats,(sailboat racing is Anguilla's national sport), it must be noted, are the descendants of those earlier fishing boats. They were usually between 17 and 20 feet in length, often with no deck and carrying one mast some 25 feet in height, on which a jib and mainsail were carried. In these boats, fishermen would go out to sea, as far north as the Old English Bank, and set their pots or fish on lines. A tradition soon developed among the boats whereby those boats which had finished hauling or setting pots would wait for the rest of the boats to complete their work so that they could all return together with added safety. Soon, a spirit of racing between the returning boats also was created. After the collapse of commercial agriculture and the beginning of mass emigration, there arose a definite need for transportation. The only mode of transportation in those days was to travel by a schooner or a large sloop. Most of the other islands in the Leeward Chain were still, in the early nineteenth century, involved in sugar production, and none had developed a local trading fleet, preferring instead to rely upon the merchant marines of their respective countries. Anguilla, on the other hand, had little direct relationship with other countries, including Britain, and was forced in earlier years to fend for itself for its transportation needs. Thus, as far back as the early eighteenth century, there were schooners and sloops on Anguilla, which in time of drought and famine, all too frequent occurrences, became a lifeline for inhabitants of the island. The art of seamanship and shipwrighting on Anguilla necessarily developed in these early years and grew stronger through time. With the migration to the Dominican Republic, Aruba and Curacao, the work of the schooners and sloops reached their golden age in terms of number of ships and trips involved. Like the fishing boats, the schooners traveled together for security. They would all leave Marigot in St. Martin with their decks full of men and baggage. The average schooner usually carried two hundred men, seeking work, on each of these trips. Life for the seamen on the schooners in many ways, was far more exciting than that of the fishermen. The voyages of the schooners back to Anguilla, for example, was the most exciting time, as the boats competed to see which could be the first to make the island. It was a constant beat for the ships to the windward, lasting from 4-20 days, and this is one of the prime reasons there is such a keen racing spirit among the boatmen of the island up through to the present time. After the collapse of the Santo Domingo trade and with the advent of diesel engines, shipments by schooners gradually diminished and boating on the island soon concentrated on fishing. Sailing boats, similar to the racing boats we see today, continued to be used for fishing until the Revolution in 1967. Around 1970, with the arrival of the outboard motor which enabled fishermen to reach their traps quickly and move among them more efficiently, fishing on the island, through to the present time has been primarily from open boats, similar to the sailing boats of yesteryear, but now propelled by outboard motors. |

|

OUR GOAL

To preserve and promote Anguilla’s Historical, Archaeological and Cultural Heritage.