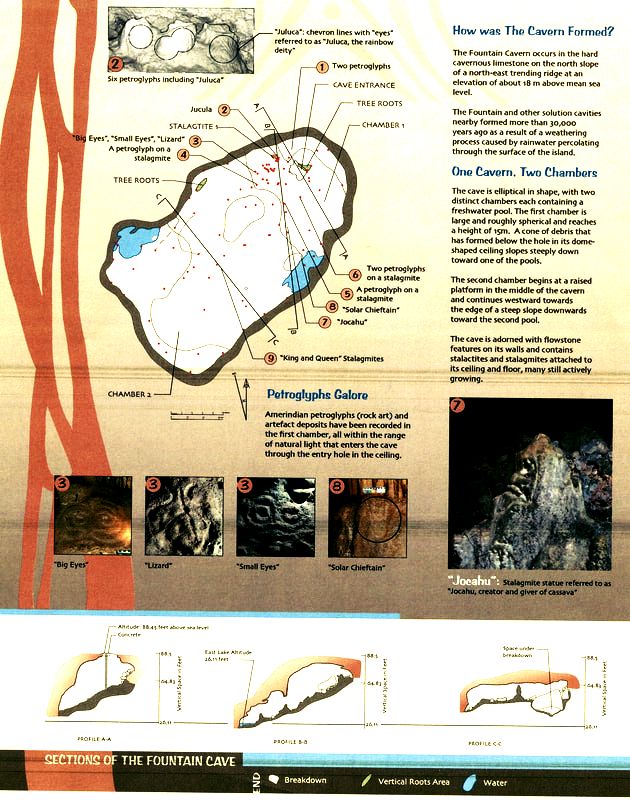

Amerindians first discovered the Cavern, or ‘The Fountain’ as it is known to locals, more than 1,500 years ago and used the cave as a source of freshwater and a ceremonial site. Historically, Anguillians also visited the cave and collected water from its pools. In pre-Columbian and early historic times, people climbed down tree roots to get from the entrance in the cave’s ceiling to the cave floor 30 feet below. A steel ladder was installed in 1953 to make it easier to access the cave and The Fountain’s freshwater. Known to be a special place for centuries, archaeologists first recorded The Fountain’s archaeological significance in 1979. Since that time, scientific field research by various individuals and insitutions, both local and international, continues to increase the understanding of the cave’s cultural significance and natural environment.

Today, Anguillians describe The Cavern as inspiring both fear and respect. Generations have known it as a place to obtain refreshing drinking water, even during the worst droughts. Generations remember visiting The Fountain as school children, even if only to peer into the darkness of the cave. Generations of lovers remember writing their names on the leaves of the Pitch Apple tree that grows in the entrance to seal the fate of their relationship.

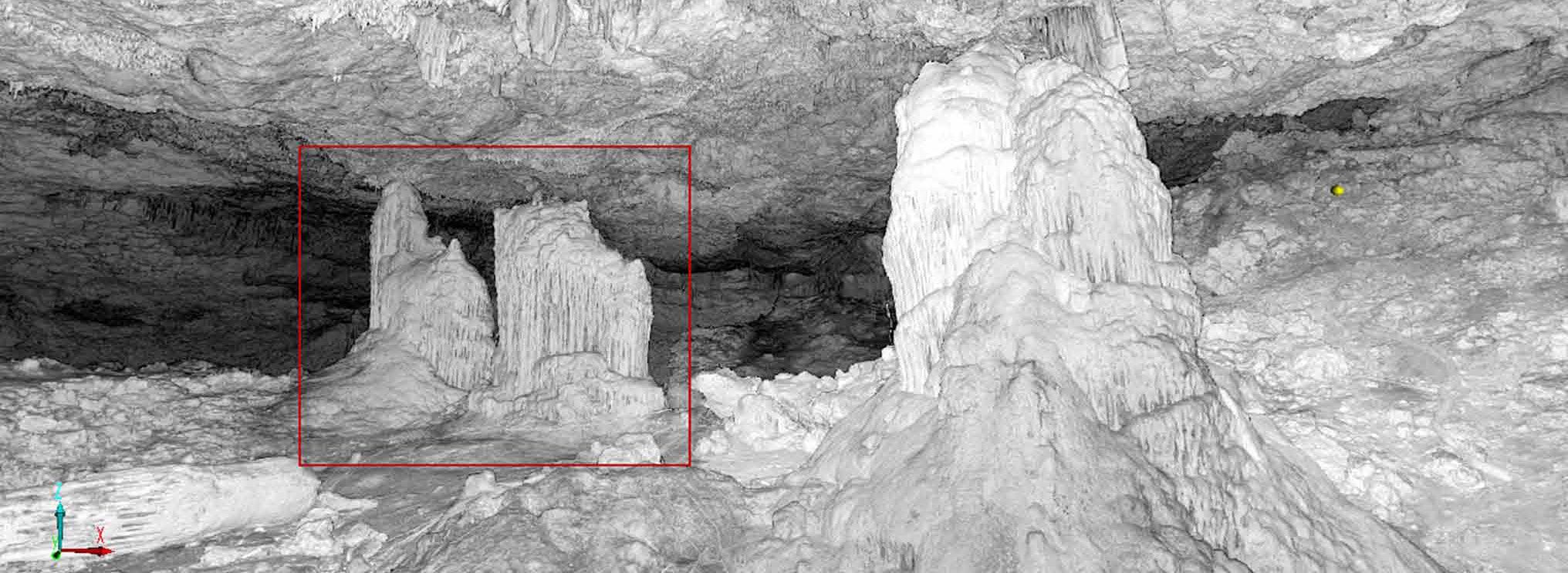

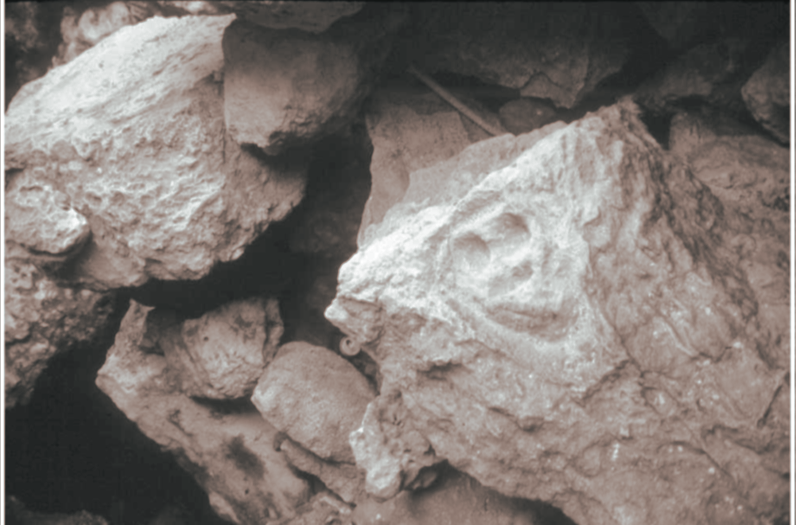

The Fountain Cavern has benefitted from various archaeological surveys since the Amerindian rock art and artefacts were first brought to the attention of archaeologists. The most notable finds include as many as 33 preserved petroglyphs, one of which is argued to represent Jocahu (or Yucahu), a deity worshipped by indigenous people of the Greater Antilles at the time of European contact in the late 1400s.

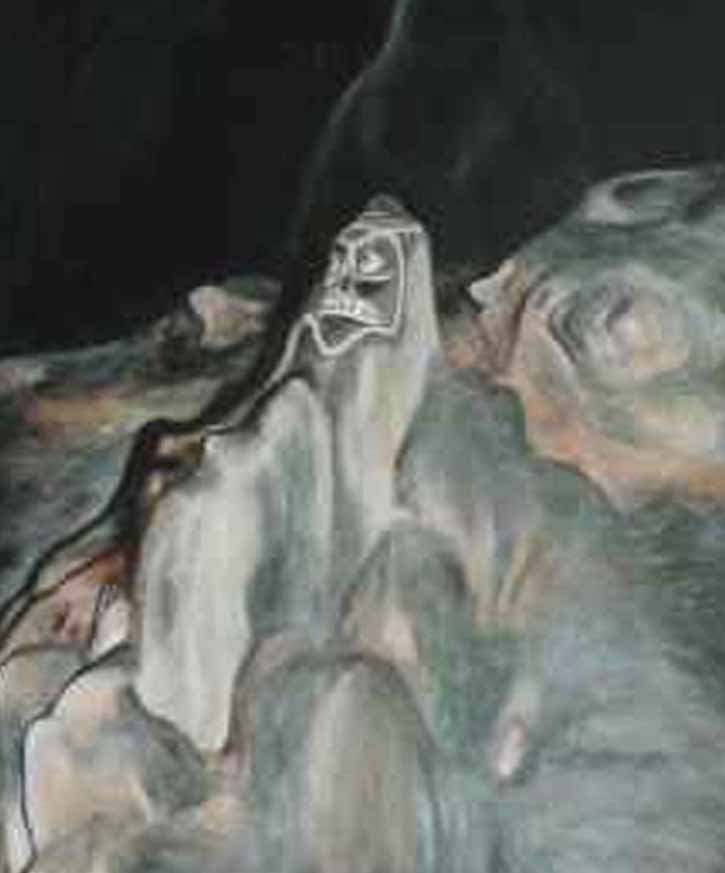

Over the years, many of the more visible petroglyphs in Fountain Cavern have been

sketched and/or given names. Appearing as faces or eyes, Amerindians used the natural contours of stalagmites to create three-dimensional works of art. Many appear to sweat in the damp, humid cave environment. Like the Jocahu “statue”, some have been described as referencing other mythological figures recorded in Spanish chronicles, such as a composite of arc and chevron lines with circular, eye indentations that has been referred to as Juluca – the rainbow deity.

sketched and/or given names. Appearing as faces or eyes, Amerindians used the natural contours of stalagmites to create three-dimensional works of art. Many appear to sweat in the damp, humid cave environment. Like the Jocahu “statue”, some have been described as referencing other mythological figures recorded in Spanish chronicles, such as a composite of arc and chevron lines with circular, eye indentations that has been referred to as Juluca – the rainbow deity.

ccording to interpretations by the Spanish, Amerindians believed that the first people

on earth, the sun, and the moon all came from caves. Caves were therefore viewed as

sacred places that connected the present with creation and with the ancestors. Caves were

used for rituals and the burial of high ranking individuals.

Archaeological research corroborates the ceremonial significance of Fountain Cavern.

In addition to the petroglyphs, many of which may represent ancestor spirit eyes and faces, thousands of ceramic sherds recovered from an area just above the first pool were from large, open serving bowls likely brought there for ritual purposes (and not only to

collect water). Based on radiocarbon dates obtained from excavations and the styles of

pottery represented, the first Amerindian use of the cave began around or before A.D. 400 and continued until at least A.D. 1200, and probably later.

on earth, the sun, and the moon all came from caves. Caves were therefore viewed as

sacred places that connected the present with creation and with the ancestors. Caves were

used for rituals and the burial of high ranking individuals.

Archaeological research corroborates the ceremonial significance of Fountain Cavern.

In addition to the petroglyphs, many of which may represent ancestor spirit eyes and faces, thousands of ceramic sherds recovered from an area just above the first pool were from large, open serving bowls likely brought there for ritual purposes (and not only to

collect water). Based on radiocarbon dates obtained from excavations and the styles of

pottery represented, the first Amerindian use of the cave began around or before A.D. 400 and continued until at least A.D. 1200, and probably later.

The Big Spring

The Big Spring site is situated in the village of Island Harbour near the northern coast of Anguilla.

Technically, it represents a partially “closed” site located within an ancient collapsed sinkhole. The

roughly circular sinkhole is about 40 m in diameter and about 5 meters deep, from the top of the

level bedrock that rings it to the surface of a large pool of water along its eastern edge. A subterranean

cavern was apparently first created underground long ago by erosion of the carbonate bedrock.

Subsequently, the “roof ” mostly collapsed, leaving the sinkhole largely open to the weather and only

partially covered in one area by a large bedrock overhang along some of its eastern and southern

edges. One or more freshwater springs occurs beneath the bedrock overhang along the eastern

edge of the sinkhole and the water seems shallow, generally only 30-50 cm deep at most, with slight

seasonal variation and supposed tidal variation as well. Large blocks of collapsed rock fill much of

the sinkhole, especially toward the northern and western edges, providing easy access across and

between the surfaces of variably sloping rock surfaces. Amerindian use of the site apparently was

focused on water acquisition and ceremonial usage in correlation with the rare freshwater. After

the Amerindians disappeared, local residents of Afro-Caribbean and Euro-Caribbean descent also

used the spring for 300 or more years throughout nearly the entire historic period. READ MORE...

Technically, it represents a partially “closed” site located within an ancient collapsed sinkhole. The

roughly circular sinkhole is about 40 m in diameter and about 5 meters deep, from the top of the

level bedrock that rings it to the surface of a large pool of water along its eastern edge. A subterranean

cavern was apparently first created underground long ago by erosion of the carbonate bedrock.

Subsequently, the “roof ” mostly collapsed, leaving the sinkhole largely open to the weather and only

partially covered in one area by a large bedrock overhang along some of its eastern and southern

edges. One or more freshwater springs occurs beneath the bedrock overhang along the eastern

edge of the sinkhole and the water seems shallow, generally only 30-50 cm deep at most, with slight

seasonal variation and supposed tidal variation as well. Large blocks of collapsed rock fill much of

the sinkhole, especially toward the northern and western edges, providing easy access across and

between the surfaces of variably sloping rock surfaces. Amerindian use of the site apparently was

focused on water acquisition and ceremonial usage in correlation with the rare freshwater. After

the Amerindians disappeared, local residents of Afro-Caribbean and Euro-Caribbean descent also

used the spring for 300 or more years throughout nearly the entire historic period. READ MORE...

Click below to read